Framing Statement

After reviewing my group’s Site Specific performance, I can confirm that Clay Walkers was greatly inspired by Antony Gormley’s work ‘Field for the British Isles’ and Robert Wilson’s ‘Walking’; we were also encouraged by Mike Pearson’s understanding and definitions of performance in his book Site Specific Performance. As a group, we initially encountered some stumbling blocks regarding what we wanted to do at our chosen sites which were Pottergate and Lincoln Cathedral Garden. We intended to devise a pathway which had a sense of pilgrimage about it and tasks to complete on the way; this we likened to Robert Wilson’s slow walk through the Norfolk countryside which was called ‘Walking’. At Saint Anne’s well there is a tale of ritual whereby someone has to walk round it 7 times and then stick a finger in one of the 6 holes in the door; a ‘good’ person will feel the devil’s breath on their finger whereas a ‘bad’ person will have their finger bitten off by the devil. We decided that this site could be compared to one of Wilson’s installations as it was a religious place en route to the Cathedral garden. As participants followed our pathway, their journey would be partly meditative and partly immersive theatre as they encountered our choice of ‘installations’. Wilson’s Walking encouraged participants to think up “rules that [they] need to break” as this fosters “feeling tranquil” (Hydar Dewachi, 2012). We too wanted the participants on our pathway to experience a similar feeling of reflection and tranquillity as they rambled along our experiential trail which was segmented by activities.

The decision to associate ourselves with Antony Gormley’s work came later on in our thinking process when we came up with the idea of working with clay at Pottergate. Antony Gormley’s “Field for the British Isles” is a multifaceted visual event whereby forward facing clay figures fill a specific space. Under his direction, people formed these little figures with their own hands. “I wanted to work with people and to make a work about our collective future and our responsibility for it” (Gormley, 2014). My idea of working with clay at Pottergate was inspired by Gormley’s work; Pottergate is a forgotten and neglected once important gateway to Lincoln and as a group, we wanted to fleetingly give it life again.

Our final performance took place on May 6th May 2015 between 9 am and 5pm. Unfortunately, because of the extremely unpleasant weather conditions, our invited participants did not turn up so we had to requisition our markers who agreed to take part in homage to the potters of Lincoln who plied their wares outside Pottergate. The pagan like ritual allegedly performed at Queen Anne’s well was included in the venture from Pottergate to the garden where an old furnace can be found built into the wall. Our modern day participants made their clay figurines just like the potters of Pottergate long ago thus bringing history into the here and now; they would then journey through the market place to the city walls where the gardens are now established.

An Analysis of Process

“Archaeology…. A process of cultural production- a form of active apprehension, a particular sensibility to material traces- that takes the remains of the past and makes something to material traces.” (Pearson, 2010, 44)

Archaeology was included in our performance as we were engaging with important historical landmarks in Lincoln such as Pottergate and the Cathedral garden, each one being marked “ by our presence and by our passing” (Pearson, 2010, 42). We wanted to create a piece which linked the past with the present by connecting an activity of long ago with something similarly performed today; this would be undertaken as part of a spiritual pilgrimage which involved rituals, misguided tours and clay making whilst following in the footsteps of the medieval potters.

Initially we were going to encompass Pottergate, Queen Anne’s well and the garden in that order.

We wanted to “take the remains of the past and [it] makes something to material traces” (Pearson, 2010, 44) hence the inclusion of ‘monuments’ such as Pottergate and the garden in the Cathedral as both are steeped in history. On their journey from Pottergate to the garden, our participants would undertake tasks on the way to show “the examination of the relationship between culture and human behaviour” (Pearson, 2010, 44). To create this relationship between the participants and these ‘monuments’ we thought about what tasks or jobs were typically carried out in Lincoln from medieval times onwards. Beth found a good source of myths and the paranormal on a website called ‘Paranormal Database’; it was here she found the legend associated with Queen Anne’s Well so we decided that as it was on the way to the garden, our participants could revive the olden time custom as a modern day ritual; this fuelled our thoughts for our final piece “as modes of cultural production, archaeology and performance might take up the fragments of the past and make something out of them in the present” (Pearson, 2010, 45).

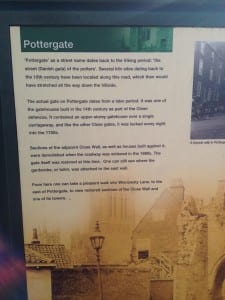

Despite many ideas being proposed, we remained constant to the one which was to highlight the history surrounding Pottergate. There is an information board besides the building but little is known about it other than it was used for “practises of labour, trade and social life” (Mike Pearson, 2010, 44). I delved into The Buildings of England. Lincolnshire by Nickolas Pevsner and John Harris book and discovered that the Pottergate area stretched from the south east to the north east corners of uphill Lincoln near the cathedral; it was the “stairway in the SW corner, now represented by the polygonal torrent, which allowed communications between the upper chamber and the gate hall” (Nicholas Antram, 1995, 484). From this we realised that it was an important communication point; a gateway where people had to state their business before being allowed into the city and where certain traders plied their wares. We did not use this as the main idea of our performance although we did use the subject of communications to stimulate our thoughts.

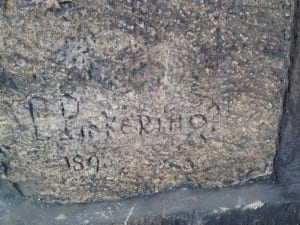

We gave some consideration to the markings on the stone at Pottergate and in particular the oldest one which reveals the name of P.Pickering and is dated 1895 (Green, 2015).

Green, G. (2015) P. Pinkering 1895. [online] Lincoln: Flickr. Available from: https://flic.kr/p/r9LZrL [Accessed on 13 May 2015].

“We deliberately ‘tag’ the environment: proclaiming and affiliations, demarcating territory” (Mike Pearson, 2010, 42).

Over the years there has been some vandalism to the archway in the form of graffiti dating from 1895 to 2010, so it is interesting to note that these old habits still continue.

Beth and I noted these markings to show how diverse they were and so we decided to start our journey at Pottergate and give the participants the opportunity to make their own mark here. This would not involve any damage being done to the building as the participants would ‘make their mark’ on post it type notes which could be attached temporarily to the archway. This linked well to another form of communication within the building’s confines whereby utility companies had ‘made their mark’ on the man hole covers situated around the building which displayed their names such as post office or telegraph. After some consideration we decided that paper notes were not environmentally friendly and would deface the building so we decided to use a more appropriate material which the participants could write their messages on.

We found it difficult to formulate our ideas for our sites especially Pottersgate, even though we were passionate to have it in our piece. I eventually discounted the idea of the participants marking their names on wood and leaving them in Pottersgate and proposed that the participants use chalk to mark the pavement around the building. Once they had written their message, they could wipe it away as though they were wiping it from their memory; that way, they start the walk with a fresh mind and a new beginning. This then kindled another idea which was linked to “Sand Mandala sculptures” (Buddhanet, 2012). The idea behind these sculptures is that the maker is “[stepping] along the path of enlightenment” and that was exactly what we wanted our participants to feel as they followed our path; it also linked very well with the concept behind Robert Wilson’s piece entitled “Walking” ((Hydar Dewachi, 2012).

The theme of pilgrimage came to mind however, we did not want our piece to be regarded as religious just because Lincoln Cathedral loomed around us so, I thought it prudent to ascertain the definition of the word ‘pilgrim’. The Oxford Dictionary says it is “Chiefly literary, a person regarded as journeying through life.” (Oxford Dictionaries, 2015) With this definition in mind, I liked the idea of our piece being an adventure of personal interest whereby the performance unfolds a story so we worked on perfecting the chalk task in Pottergate and the ritual at St Anne’s well. The chalk task was to encourage participants to think of a wish or a memory that they would like to physically mark on Pottergate’s pavement as a temporary memorial to it. At St Anne’s well, we wanted to create our own version of the age old ritual performed there so we came up with new moves to execute when going round the well such as ‘placing your hands on the roof’, ‘turning around and shouting the first thing you see in your surroundings’. Unfortunately, we could not agree on anything other than to go with the misguided tour idea from Pottergate to the cathedral garden which involved us telling genuine and phony stories about each place. I was unsure about the meaning of a ‘misguided tour’ and so I researched the internet; I found some interesting facts including the staging of a Fools Festival (Fool Festival, 2013) which is very popular with the public and involves the telling of ‘hidden stories’ which describe an event based on some facts and some fiction. I liked this idea so I looked for a clear description of a misguided tour and found this explanation:

“We like to blur the distinctions and play across the boundaries of the real and the fake…They will amuse you with their irrelevant insights and entertain you with their opinions on everything but the hard facts” (Fool Festival, 2013). After some discussion, we eventually came to the conclusion that this was not exactly what we were aiming to do and was not very appropriate for our sites and our lecturer concurred with this.

Our next idea was to use the information on the board at Pottergate; we found out that it was “built in the 14th century” (Green, 2015) yet “Pottergate as a street dates back to the Viking period: ‘the street (Danish gata) of the potters’” (Green, 2015).

Green, G. (2015) Description of Pottergate. Lincoln: Flickr. Available from: https://flic.kr/p/rxsM4R [Accessed on: 13 May 2015].

After reading this we decided we could build a misguided tour around the oldest marking on Pottergate’s wall which is by P.Pickering. He would be a potter and we would follow his life until he succumbed to the plague. This would link well with actual historical facts for the area and kindled a pooling of ideas amongst my group members. Our main aim was to enable the past to overlap with the present and our ideas were helping us to bring this to fruition so we could “Demonstrate for the popular imagination how we ourselves and our immediate environment are the part of the historical process, how constituents of material culture exist within overlapping frames and trajectories of time, drawing attention to how we are continuously generating the archaeological record” (Pearson, 2010, 45).

When it came to the time for us to explain to our module leader what we were aiming to do he listened intently and watched our piece with interest however, when we talked it through afterwards he had some reservations. He commended the idea of making clay models and taking them from Pottergate to the garden but condemned the ritual enactment at Queen Anne’s well. He did suggest however, that we take the concept of a ritual into the journey of the clay.

So now we were only working with two sites and needed to consider some artists who work with figures to ensure we remained true to our idea that “we are continually generating the archaeological record” (Pearson, 2010, 45). We wanted the participants to create something which represented a little of themselves so as to continue the history of the places by contributing their work to them and thereby leaving a little bit of themselves behind.

Antony Gormley’s sculptures are recognised all over the world with his most famous one probably being the ‘angel of the north’ (Gormley, 2015) however, his piece entitled ‘Field for the British Isles’ is the one which has inspired us because it was created by volunteers. Every person made one terracotta figure which was then placed in a room from corner to corner, end to end. When you look at their faces, you feel accountable for each and every one as they constantly stare back at you because, as Gormley points out, we are “responsible for the world that it [FIELD] and we were in” (Gormley, 2014).

Having figurines spread all over the cathedral garden would bring a dramatic end to the journey our participants began in Pottergate. Forming their own images in salt dough (more environmentally friendly than clay) and taking them to their final resting ground would I feel, emulate the theatricality of Gormley’s work and impact on the garden and the participants themselves. As Pearson says in his Site Specific Performance book, the “French archaeologist Laurent Olivier has termed a ‘relationship of proximity maintained regarding places, objects, ways of life or practices that are still ours and still nourish our collective identity’” (Pearson, 2010,43). We made an impact on those places and developed a “relationship between material culture and human behaviour” (Pearson, 2010, 44). These places are often neglected or ignored so the public should be reminded of their heritage and popularity in their heyday. Using salt dough figures and following a path between the hidden gems of Pottergate and The Cathedral Garden definitely gives you a connection to the piece and a feeling of responsibility.

Green, G. (2015) Complete Collection. [online] Lincoln: Flickr. Available from: https://flic.kr/p/rWJYYD [Accessed on 13 May 2015].

Before rehearsing the performance, we copied Antony Gormley’s idea and made 190 salt dough figurines for the 9 till 5 rehearsal. We found it uncomfortable rehearsing in public and attracted some funny looks from people; we were really out of our confident zone but we carried on and got what we wanted out of it as well as realising we must take weather conditions into consideration and be prepared for all types. We also thought it would look more professional if we sited a table and chair at Pottergate with signs explaining what we were doing and saying ‘clay walkers in progress. When we placed the figurines on the stonework of the fire furnace in the garden, it really did loosely resemble Gormley’s work. There was a definite connection between the models and the sites and my own understanding of Site Specific was improved; we had engaged “intensively with the history and politics of that place, and with the resonance of these in the present” (Pearson, 2010, 10) As a group we had rediscovered two amazing locations and by placing our little figures within them I had been given an insight into the relationship between site and performance and could now understand why holding performative events in unusual locations is so enthralling. Our performance as potters was a bit scary at first, but it was a great way of introducing us into the world of Site Specific and it was fun to watch the public reaction to it; it was a very positive experience as we helped “the past to surge into the present” (Pearson, 2010, 10).

Performance Evaluation

Green, G. (2015) Final Site. [online] Lincoln: Flickr. Available from: https://flic.kr/p/rTykuL [Accessed on 13 May 2015].

Our final performance was difficult because of the poor weather conditions, the high risk of slipping on the wet stone slabs in Pottergate and the constant stream of traffic around the Pottergate area in general. In the early afternoon, Sophie was nearly accosted by a passer-by on a bike so we moved up to the garden to finish off the performance. It was definitely a bit of a struggle to perform under such conditions but it was nevertheless very rewarding. When our assessor and module leader visited they commented on how they would have liked to have seen more than just the figures to show that we were taking “up the fragments of the past and something out of them in the present” (Pearson, 2015, 45).

We conceived, devised and staged our performance and made theatre in a location steeped in history; this not only showed its versatility as a place but also how it could be reconnected with its original purpose. This links well with what Gormley says about his ‘field’ project, “I like the idea of the physical area occupied being put at the service of the imaginative space of the witness” (Gormley, 2015).

Our only two actual audience members were our assessors but fortunately their reaction to each piece was good; they found it interesting and gave positive comments about it so we are confident that we managed to create a unique piece which incorporated and appreciated the history of the sites in all their glory. The “audience need not be categorised, or even consider themselves, as ‘audience’, (but) as a collective with common attributes” (Pearson, 2010, 175).

The difficult weather conditions undoubtedly hampered not only our performance but our props as the salt dough became soggy nevertheless, creating the memories of this piece was rewarding as we saw our pathway “overlapping frames…of time” (Pearson, 2010, 45). It soon became obvious to us that the public do not respect the Pottergate area or recognise its importance in the past as they go about their business and they certainly were very unsure about approaching us to see what we were doing. Siting the table and chairs helped to reassure the public that we were not doing anything untoward as we moulded the multicoloured salt dough; it also gave a purpose to our work and enlightened the public about performance outside the auditorium.

Green, G. (2015) Final Performance. [online] Lincoln: Flickr. Available from: https://flic.kr/p/smEPxm [Accessed on 13 May 2015].

Site Specific performance in contemporary theatre is ever growing and my understanding of it is that it encourages thinking out of the box; it asks why? and what happens if I do this? And, as Mike Pearson explains “site specific involves an activity, and audience and a place then creative opportunities reside in the multiple creative articulations of us, them and there” (Pearson, 2010, 19). It makes people think and look at a place they know well in a new way just as we did by making the garden a monument to the potters of long ago and reminding the people of today of its importance and original purpose or by making metaphorical bricks from salt dough so people could make their mark on them just as they did on the bricks on the Pottergate arch as far back as 1895. “These marks we make, these traces we leave, are ineffably archaeological: ‘an archaeological of us’, of contemporary material culture, of the recent, of the immediate” (Pearson, 2010, 43) and it is this relationship with the site which is so unique to Site Specific Performance.

Bibliography

Antram, N. (eds) (1995) The Buildings of England. Lincolnshire. London: Penguin.

Buddhanet (2012) Chart of the Elements in Kalachakra Sand Mandala. Tullera: Buddhanet. Available from: http://www.buddhanet.net/kalimage.htm [Accessed on 13 May 2015].

Gormley, A. (2014) Field, 1989 – 2003. [online] London: Antony Gormley. Available from: http://www.antonygormley.com/projects/item-view/id/245#p0 [Accessed on 19 April 2015].

Green, G. (2015) Complete Collection.[online] Lincoln: Flickr. Available from: https://flic.kr/p/rWJYYD [Accessed on 13 May 2015].

Green, G. (2015) Description of Pottergate. [online] Lincoln: Flickr. Available from https://flic.kr/p/rxsM4R [Accessed on 13 May 2015].

Green, G. (2015) Final Performance. [online] Lincoln: Flickr. Available from: https://flic.kr/p/smEPxm [Accessed on 13 May 2015].

Green, G. (2015) Final Site. [online] Lincoln: Flickr. Available from: https://flic.kr/p/rTykuL [Accessed on 13 May 2015].

Green, G. (2015) P. Pinkering 1895. [online] Lincoln: Flickr. Available from https://flic.kr/p/r9LZrL [Accessed on 13 May 2015].

Hydar Dewachi (2012) Robert Wilson “Walking” [online video] Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T8ih4GddMc4 [Accessed 10 May 2015].

Pearson, M. (2010) Site-Specific Performance. 1st edition. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan ltd.

Oxford Dictionaries (2015) Pilgrim. [online] Oxford: Oxford Dictionairies. Available from: http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/pilgrim [Accessed on 13 May 2015].

Fools Festival (2013) Misguided tours. [online] Belfast: Fools Festivals. Available from: http://www.foolsfestival.com/2013/misguided-tours/ [Accessed on 13 May 2015].

Fuse Performance (2015) Misguided Tours. [online] UK: Fuse Productions. Available from: http://www.fuseperformance.co.uk/fuse_Performance/Gallery/Pages/Misguided_Tours.html [Accessed on 13 May 2015].