Framing statement

Nothing Happens Here Apart From Us is a site specific performance which is taking place in Castle Square, Lincoln, on Wednesday 6th May 2015. There will be three performances, all being half an hour long, beginning with 9am – 9:30am, then 12:30pm – 1pm and finally 5:30pm – 6pm. Nothing Happens Here Apart From Us is a piece that explores the notions of CCTV and political power in order to conduct a social experiment in a local context. The aim is to explore and gather information on the behaviour of people using the space when they are openly being observed, in which we will record on a personal level and further advance to a wider system.

Our methodologies include the use of liminal space, pervasive media, documentation and a choreographed structure in order to appear as a larger system. Our piece echoes a political theme, which at first was only coinciding with the fact that our interest was towards the notions of privacy and how the abundance of CCTV cameras in this nation abolishes it. It quickly progressed due to the fact that we realised our performance was the day before the 2015 general election and became a main topic in which our work was closely related to.

During our performance we will be using maps to draw the routes that people take across the space. The space in which we map is the liminal space of the Castle Square, which people mainly use as a crossing to get to their destinations. Our tracks stop printing at the exits and entrances of the space, likewise; when we take the route ourselves, we stop at what can be interpreted as an invisible boundary. This is because we are part of the larger scheme and it is where the perimeter ends for the CCTV.

The use of a live feed will be actioned with a GoPro camera and IPad, which will allow the audience to see the space from the view of a CCTV camera operator. The two group members holding the system will be classed as the ‘hub’ and will move accordingly depending on the when the CCTV camera moves. They will therefore be controlled by a higher political power within our own circumstances. The tracks and information that the map drawers gather will be the feed to the bigger system. Every time that there is no one to follow, the map drawers will return to the base and resume when they see someone else. We will use this scenario in comparison to a larger scale version, which is how the CCTV all over England is fed into the government system which is used accordingly.

The influences which helped frame this piece consist of both individual and group theory and practice. The works of Mike Pearson and Emma Govan where the main contributors towards beginning the process as we used exercises that can be made relative to a space. Other inspirations involve the Surveillance Camera Players, Tehching Hsieh and the Panopticon concept.

We chose not to advertise our piece as it was dependent on an accidental audience, because if we knew we had people coming to see it their presence will ultimately be false as they weren’t going to be there naturally.

An Analysis of Process

Initial exercises

During the first workshop of Site Specific Performance, we were invited to explore ‘subtle mobs’ which consists of various instructions for those in a specific space. The version that the class received incorporated a section instructing us to ‘locate and gather proof of the following’ which consisted of one suggestion in particular that caught my attention; ‘an escape to the roof’. The outcome I was so busy looking for was right under my nose, and arrived through divine intervention. In The Place of the Artist Emma Govan explains that ‘Within contemporary performance, site-related work has become an established practice where an artist’s intervention offers spectators new perspectives upon a particular site or set of sites.’ (Govan, 2007, p.121) This was thought provoking; an artist’s intervention doesn’t simply have to be showing someone a new way of looking at something, it can be made through suggestion, timing and a sort of planned, hopeful coincidence of recognition. In this case, the instruction of gathering proof suggested a photograph, in which offered a new perspective seen through the camera lens to get the result I was looking for.

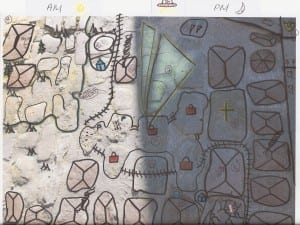

This new perspective was carried out through other tasks in the forthcoming weeks, and played a big part in the process of our performance. It helped another group member and I create an unconventional map of our site, in which we used a picture of the stone floor as a bird’s-eye view to create a small village based on the depths and shapes of the stones. We took inspiration from the artist Slinkachu who is a photographer that creates installments using miniature figures in life size settings in order to create a perspective photograph, whose blog can be viewed here: http://little-people.blogspot.co.uk/

Photo: (Hind, 2015) Photo: (Hind, 2015)

Above is my creation, and I figured that there was no need to be 100% realistic in what I was doing and this allowed the simplest of things to become important. This notion has become very relevant and useful in site specific performance as it has taught me to look beneath the view.

Arriving from the theme of not having to be realistic, our initial idea was based around the Cathedral where we would do a mythology based misguided tour. Our mythology stemmed from pictures and thoughts we had toward historical aspects. One of our main focuses was the use of time within our piece, as we wanted to explore how things happen over a time period, which lead us to the idea of using time-lapse videos. After much discussion and feedback, we realised that a lot of what we were doing already existed in forms of ghost walks hosted in Lincoln Castle Square. To avoid similarity and to ensure that our idea was original we decided to move away from the idea completely, which included moving away from the Cathedral too.

To get some new inspiration we decided to use Mike Pearson’s ‘Some Exercises Towards Relating Space’ in the livelier Castle Square. An exercise that stood out to us the most was in section three, asking us ‘After visiting a location: What would you have remembered had you gone there without a camera?’ (Pearson, 2011) We all agreed that the one thing we all noticed was the large CCTV camera situated on the front of the Magna Carta Pub.

Progression

Using this feature, we looked into the implications of CCTV, gathering facts to shape our idea. ‘The British Security Industry Authority (BSIA) estimated there are up to 5.9 million closed-circuit television cameras in the country.’ (Barret, p. 2013) And Nick Pickles suggests within the newspaper article that ‘With potentially more than five million CCTV cameras across country … we are being monitored in a way that few people would recognise as a part of a healthy democratic society.’ (IBID) Our motive became about raising awareness of the fact that we are an incredibly highly watched nation, and from this we created a social experiment in which we would explore the behaviour of people when they are openly being watched by others in public.

We began by observing the CCTV camera on how often it moved and what was in view at different angles. From this, we decided to set up our own recording equipment to film using the effect of time-lapsing, to mimic and create our own CCTV, which on the performance day would be shown back to the audience via an IPad. This was to go against the usual limitations of being recorded on CCTV and never getting the chance to see it back.

However, after receiving feedback that we would never realistically embody the CCTV camera, we decided to use this as secondary documentation. We acknowledged that the best way to intrigue the audience is by being so engaged in our own work, instead of staging something for the audience. This produced an idea that we should perform to the camera itself, which quickly became labelled a ‘CCTV Ballet’. This broadened the experience of working with CCTV as we were able to connect on another level to the operator and it became about being controlled by an unseen force. The inspiration to perform to the camera came mostly from a group called the ‘Surveillance Camera Players’. On a 1984 performance video they quote ‘The surveillance camera Players are not watching you. They are watching the cameras, because we have forgotten to.’ (Surveillance Camera Players, 1984) To watch this video follow this link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RILTl8mxEnE

The idea was to retrieve the footage and involve it in our final piece, however when we applied to get it from the Council, it was going to take up to forty days minimum. We couldn’t rely on the chance that it would arrive in time and again, had to use this as secondary documentation along with our time-lapse videos. If the tape doesn’t arrive until the assessment period is over, the tape still counts as a process, and will be external documentation that will continue to exist outside our performance.

In the end, we resorted to a live stream of video, in which we would use technologies to portray a tunnel of surveillance created in the space which made our piece more interactive.

Photo: (Nothing Happens Here Apart From Us, 2015)

Also, to counterbalance the space on a personal level, we referred back to the use of perceptions in our early lessons of Site Specific Performance and used mapping to track people’s personal routes which lead to their destinations. We selected a piece of the site in which we overlapped a bird’s-eye view map of the entrances and exits to the space.

Our group shared a lot of the same traits as the Surveillance Camera Players, but also differed in the sense that we were mimicking the traits of a CCTV system to raise awareness, while they performed to it. This created slight differences with our pieces due to our audience. With the Surveillance Camera Players, they wanted the message to go straight to the higher power, whereas we want our audience to acknowledge, interact and become involved with our piece whilst it was being received by the operator.

Other forms of documentation were compiled through pictures of the process, which involved dual layers of time. Documentation was an important aspect of our performance and we wanted to make sure that we had lasting, external evidence of us performing. The idea of representing layers of time arrived from the artist Tehching Hsieh, where the performative act of documentation was his performance. The result of the collected documentation at the end was just an exhibition for his works. The performance we studied and took inspiration from was his One Year Performance 1980 – 1981. A Video of this work can be viewed at this link https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tvebnkjwTeU

We used similar traits to Hsieh in the forms of documenting our process for it to be external, though he underwent his method in isolation as opposed to us wanting to be in the public arena as we were interested in reactions. This is because, as our piece was progressing, the site was becoming ‘…a ‘potential’ space, a place for enquiry and invention.’ (Pearson, 2010, p.25)

FINAL DRESS REHEARSAL

Our dress rehearsal ran with no technical hitches, although it appeared to confuse some of the spectators. I personally had a gentleman mistake my clipboard of tracking as a drawing when I was stood waiting for someone else to follow. We also had no interaction with each other as a group and didn’t really seem to connect which affected the flow of the performance.

After our rehearsal, we received some feedback that would solidify our connection of the mapping and the CCTV tunnel. To achieve the appearance of a system, it was suggested that we should work on our body language during the performance. For the group members holding the tunnel, they would stand back to back and rotate in sync depending on where the camera moves. This was in order to appear as a mechanism similar to the camera. We decided that there would be no or very little interaction with the audience, and we would create flyers to point them to out blogs and Flickr site which would hold the results. This would help us achieve ‘…a creative act of interpretation and intervention, all of which depend on where you are standing, when and for what purpose…’ (Heddon, 2008, p. 91)

For the people drawing the maps it was agreed that we would all have a uniformed clipboard, in which we would hold up whilst tracking and following, and hold it by our sides when we were ‘inactive’. This made sure that our actions were unified and consistent, and also made our clipboards tools to the piece rather than an interest. If the mappers couldn’t follow anyone for more than 1-2 minutes we agreed that we would return to the ‘hub’ to provide a physical connection to the other members.

The link with the panopticon concept was created when we were looking at the behaviour of people when they know that they are being observed. The concept exists in a circular prison structure designed by Jeremy Bentham where the prisoners can be seen at all times by the guards. The guard couldn’t have been watching every prisoner all of the time but that had an effect on the prisoners’ behaviour greatly, as they didn’t know when they were being observed. The structure was described as ‘…a mechanical contrivance to obtain and exercise power…’ (Semple, 1993, p.10) This ideology was echoed in our performance through metaphors, as the members holding the CCTV tunnel were rotating in circular motion representing the guards. The view of the camera represents the view of the prison guard, which makes the public the prisoners as they don’t know for sure whether they are view of the camera which makes their behaviour change. The behaviour varied from looking the other way, to acknowledging the camera and feeling quite angry or annoyed which can be noticed in the way they walk past or discussed with acquaintances.

A Performance Evaluation

As a result of performing at three peak times of the day, we were able to get a diverse set of results in which we can relate and compare. The results varied in terms of audience intrigue and routes in which they walked, which was controlled by factors such as bad weather, busyness and where they needed to be at what time. Because the audience participation was more accidental rather than active, the numbers of people that would be involved were highly interchangeable and unpredictable which meant that the results at first glance may seem a bit bleak. This factor however was not seen as a downfall, rather as a means of further interpretation.

9AM – 9:30AM

On the first performance, our well tested and rehearsed technology well and truly failed us. Within minutes the group were forced to improvise, and although our intentions of being able to see the site through a tunnel of technology were compromised, we were still able to record and reflect in our space. The audience were mostly rushing, using the space as an obligatory crossing and the patterns were similar. While most of the reactions were towards the ‘hub’, there was a comment towards a person drawing the maps of tracks. It came from an elderly lady saying “people are so nosey nowadays”, which is ironic seeing as though the comment was said toward a person with a clipboard and not the people presenting a camera twenty meters away. The debateable question is whether the lady noticed that the single person was part of the larger scheme and aimed it at the group as a whole, or at what may have appeared an authoritative figure collecting information, which in the grand scheme of things is no different to what the CCTV camera operator is doing for the government. What presumably made her behave that way was our obvious act of recording.

12:30PM – 1PM

The second performance was under similar circumstances, in which the technology failed us. However the audience, in bigger numbers, were not using the space as a crossing so much, but a place to wait and gather. This meant that the audience had their own business to go about and did not give a lot of attention to us, although our presence was noticed. Interactions consisted of wanting more information in which flyers were given, and an appreciative comment towards the name of our piece.

5:30PM – 6PM

Our technology worked and it was the weather that failed us this time, as it rained for the duration of our final performance. Surprisingly, this made for interesting results, as when the audience hurried inside pubs and shops they wondered why we were still stood there which only affirmed our presence and meaning. We had a whole new level of audience in which the main unseen operator of this system did not see. The only comment we received was “have you been here all day? I saw you this morning when I went past!” which offered us a whole new appearance from his point of view. This put us on a whole new level of symmetry with the CCTV operator in which we appeared to be working the same standard working hours. Although we knew the hours we were present, us as citizens do not know when the operator is present, which is relates to the intended ‘panopticon’ concept.

In order to view our process pictures, mapping results and video clips of the day please follow this link: https://www.flickr.com/photos/nothinghappenssite/albums

I believe that where we were situated played a great part in the success of the performance, as we were quite plainly unavoidable. Overall, our performance could have been improved by our technical aspects, which would involve less reliance and a contingency plan. If we were to do this again, I would have definitely used the time more wisely in the sense that we could have incorporated useful elements like the CCTV ballet. My engagement with site specific theory and practice has broadened my awareness of the types of audience in particular. As experienced in this performance, the audience can be accidental, and the dependency on the audience type can change an entire meaning of a performance which in this case isn’t achievable in a traditional theatre.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barret, D. (2013) One surveillance camera for every 11 people in Britain, says CCTV survey. The Telegraph, 10, July. [Accessed 5th March 2015]. Via http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/10172298/One-surveillance-camera-for-every-11-people-in-Britain-says-CCTV-survey.html

Das Platform (2014) Tehching Hsieh: One Year Performance 1980-1981. [Online video] Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tvebnkjwTeU [Accessed 10/05/15]

Govan, E. Et al (2007) Making a Performance: Devising Histories and Contemporary Practices London and New York: Routledge

Kuparanto (2006) Surveillance Camera Players: 1984. [Online video] Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RILTl8mxEnE [Accessed 9/05/15]

Heddon, D (2008) Autobiography and performance. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hind, L (2015) Photostream [Flickr] 28th May. Available from https://www.flickr.com/photos/130878920@N06/with/16050990094/ [Accessed 15/05/15]

Nothing Happens Here Apart From Us (2015) Nothing Happens Here Apart From Us [Flickr] Available from https://www.flickr.com/photos/nothinghappenssite/17173050187/in/album-72157652314713146/ [Accessed 15/05/15]

Pearson, M. (2010) Site-specific performance. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan

Pearson, M. (2011) Some Exercises Towards Relating Space. [online] Available from https://blackboard.lincoln.ac.uk/…/Mike%20Pearson%20… [Accessed 6th March 2015] via https://blackboard.lincoln.ac.uk/bbcswebdav/pid-953326-dt-content-rid-1863756_2/courses/DRA2035M-1415/Mike%20Pearson%20%203bplaceexercises.pdf

| Semple, J. (1993) Bentham’s prison: a study of the panopticon penitentiary. New York: Oxford University Press |

Slinkachu (2006) Little People – a tiny street art project. Available at: http://little-people.blogspot.co.uk (Accessed: 15 May 2015)